Earlier this year, a study by Duke-NUS Medical School and the Institute of Mental Health found that Singapore was losing around $16 billion a year to anxiety and depression, with only about a third (32%) seeking healthcare to treat their conditions.

Earlier this year, a study by Duke-NUS Medical School and the Institute of Mental Health found that Singapore was losing around $16 billion a year to anxiety and depression, with only about a third (32%) seeking healthcare to treat their conditions.

A similar proportion of students and adults was found to be affected by symptoms of these conditions, and the conditions significantly affected the performance of both students and adults.

The Covid-19 pandemic and the rising costs of living in recent years are likely to have exacerbated the mental health pressures that individuals face, leading to the suicide rate in Singapore reaching its highest in more than 20 years in 2022. In recognition of these trends, the Government created an Interagency Taskforce on Mental Health and Well-Being, which aims to enhance the mental health and well-being of Singaporeans.

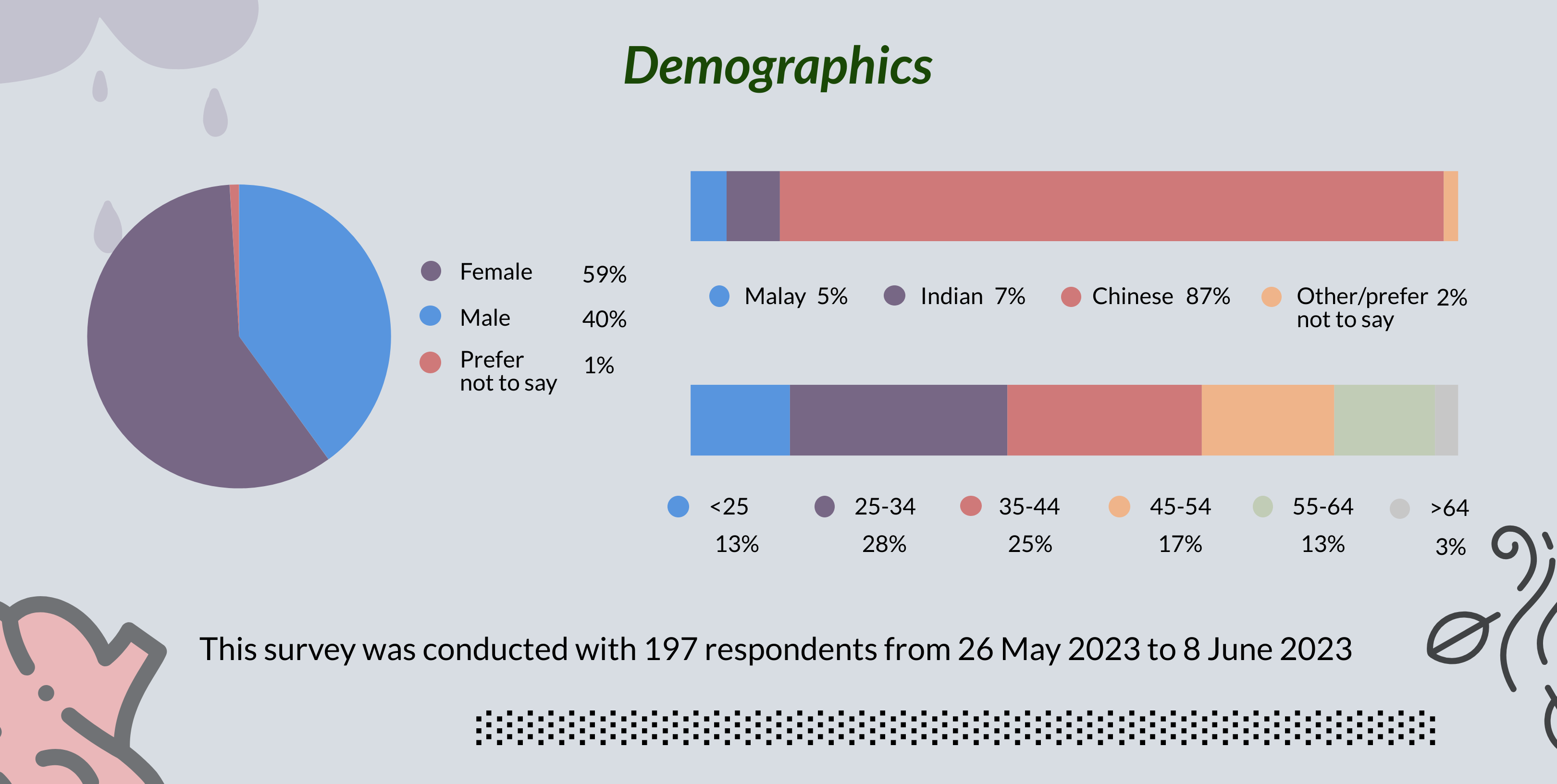

Given the growing emphasis on mental health and the low rates of healthcare utilisation, we conducted a survey to assess views towards mental health in Singapore, as well as the habits of Singapore residents in managing their mental wellness.

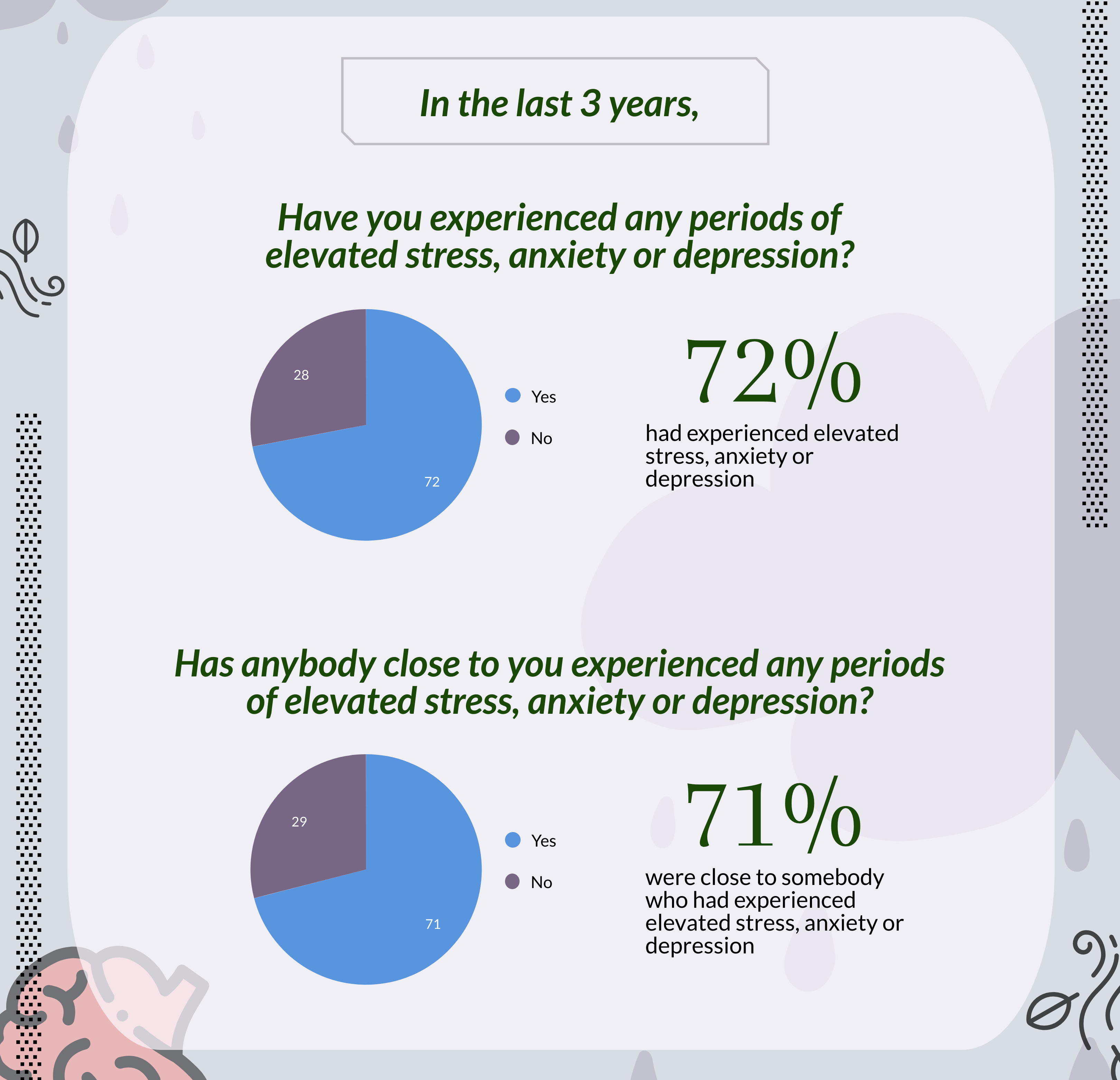

Duke-NUS’s study found that 14% of respondents had symptoms consistent with depression and 15% of respondents had symptoms consistent with anxiety. These results, however, do not necessarily capture the full image of mental health in the community, as studies have found that at least half of those who suffer depressive episodes go on to have additional episodes in their lifetime. Seeking to investigate the occurrence of episodes of poor mental health, we asked respondents if they had experienced elevated stress, anxiety or depression in the last 3 years.

While self-reporting may not be the most accurate way to diagnose individuals, the results showed that a large majority of respondents had experienced poor mental health in the last 3 years, roughly coinciding with the beginning of Covid-19 restrictions. These results were consistent with the proportion who were close to someone who had experienced poor mental health, indicating that this has been a challenging period for many Singaporeans.

Though respondents reported periods of poor mental health in recent years, they also overwhelmingly reported placing a high degree of importance in their mental health. 95% of respondents said that their mental health was either highly or extremely important (4 to 5 on a 5-point scale). However, there was a general sense that society did not place a similar emphasis on mental health, with only 41% of respondents feeling that society perceived it to be highly or extremely important.

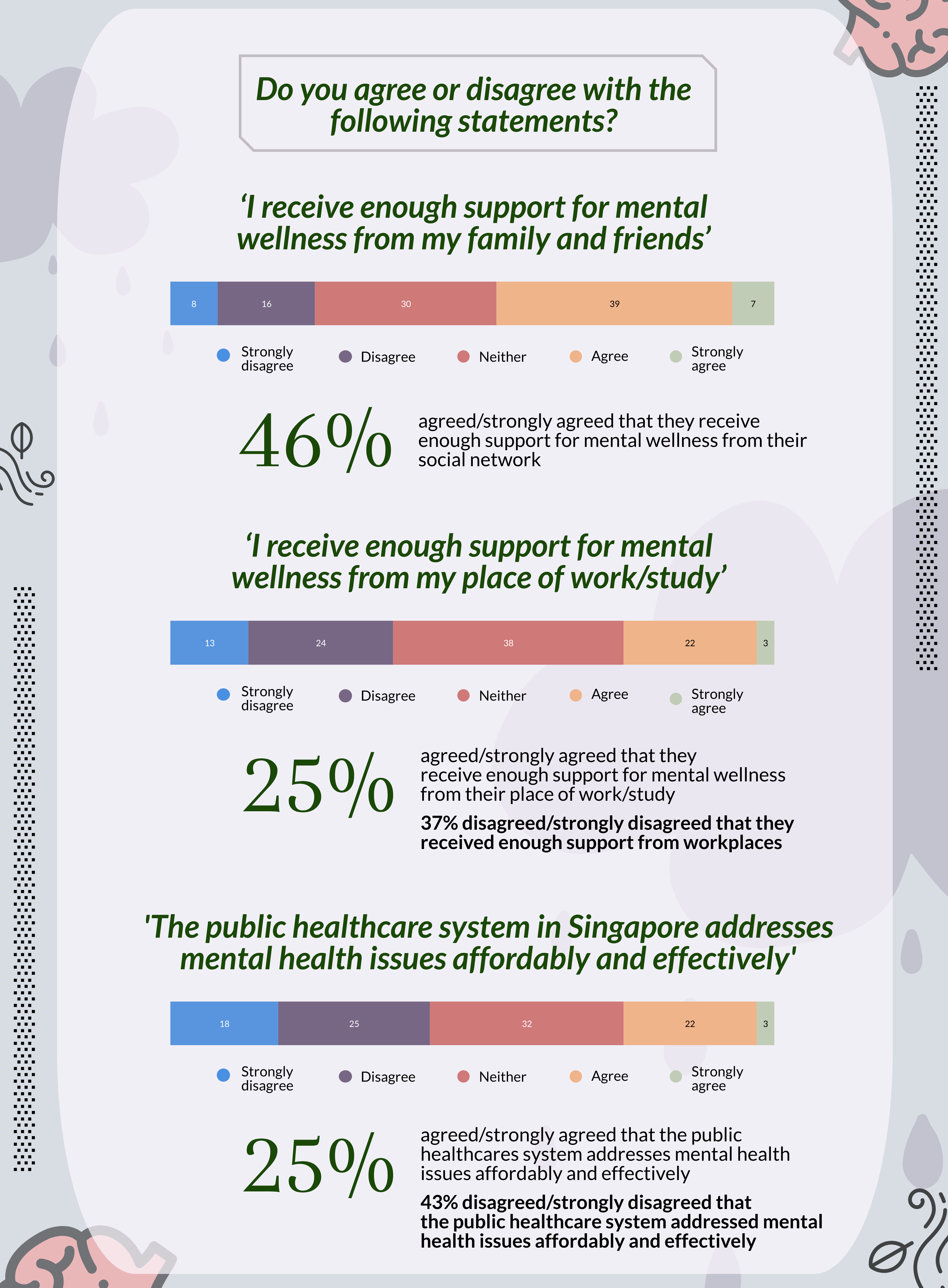

A possible reason for the divide between individual perceptions and societal perceptions of mental health could be the level of support that Singaporeans receive. 46% of respondents indicated that they received enough support for mental wellness from family and friends, who often provide the initial network for support. This proportion was far higher than the number who felt supported at their place of work or study (25%).

Respondents were more likely to disagree/strongly disagree rather than agree/strongly agree that they felt supported at work or school. These results were mirrored in views of the public healthcare system, with 43% who disagree/strongly disagree that the system addressed mental health issues affordably and effectively while only 25% agree/strongly agree.

Such findings may suggest that mental health is still viewed predominantly as a personal issue in Singapore. Individuals may still be unable or unwilling to find support from society more broadly, and there may be insufficient focus on mental health by organisations when considering worker and student welfare.

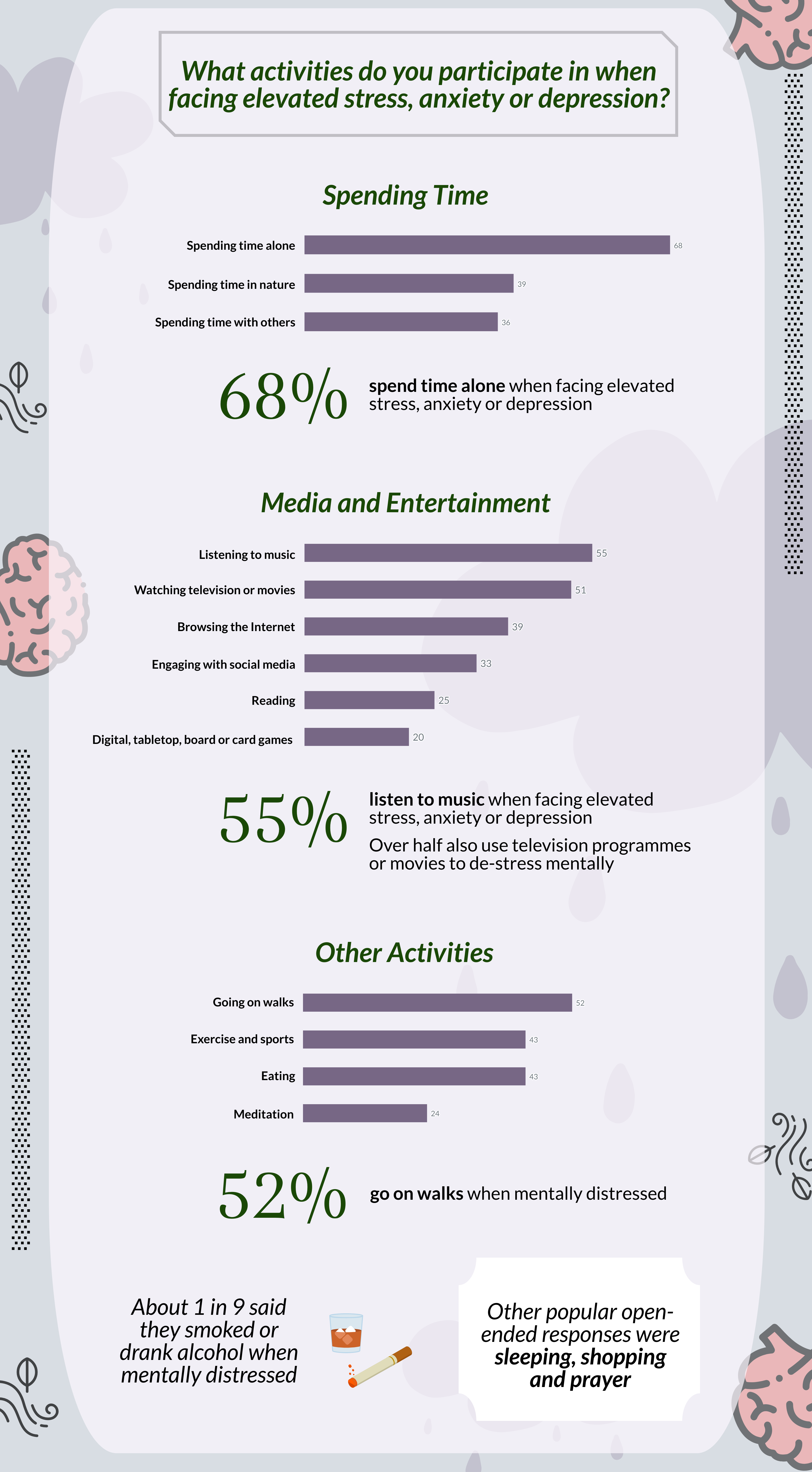

When questioned on the activities they would participate in when facing poor mental health, the largest proportion of respondents said that they preferred to spend time alone (68%). While this may be an effective method of managing stress in Singapore given our high population density, social isolation can also contribute to poor mental health.

Significant proportions of respondents also reported using media, with the most popular being listening to music (55%) and watching television or movies (51%). A third or more would also browse the internet (39%) or engage with social media (33%).

While these activities may not in themselves be harmful, they may lead to unhealthy dependencies and habits that perpetuate poor mental health. Social media use, for example, has been linked to a tangible drop in life satisfaction in teenagers while also contributing to sleep deprivation, which itself can increase the risk of anxiety, depression and self-harm.

More than 2 in 5 also would eat when facing poor mental health though diet is linked to mental health, and 1 in 9 admitted to smoking, drinking or using other intoxicating substances when facing poor mental health.

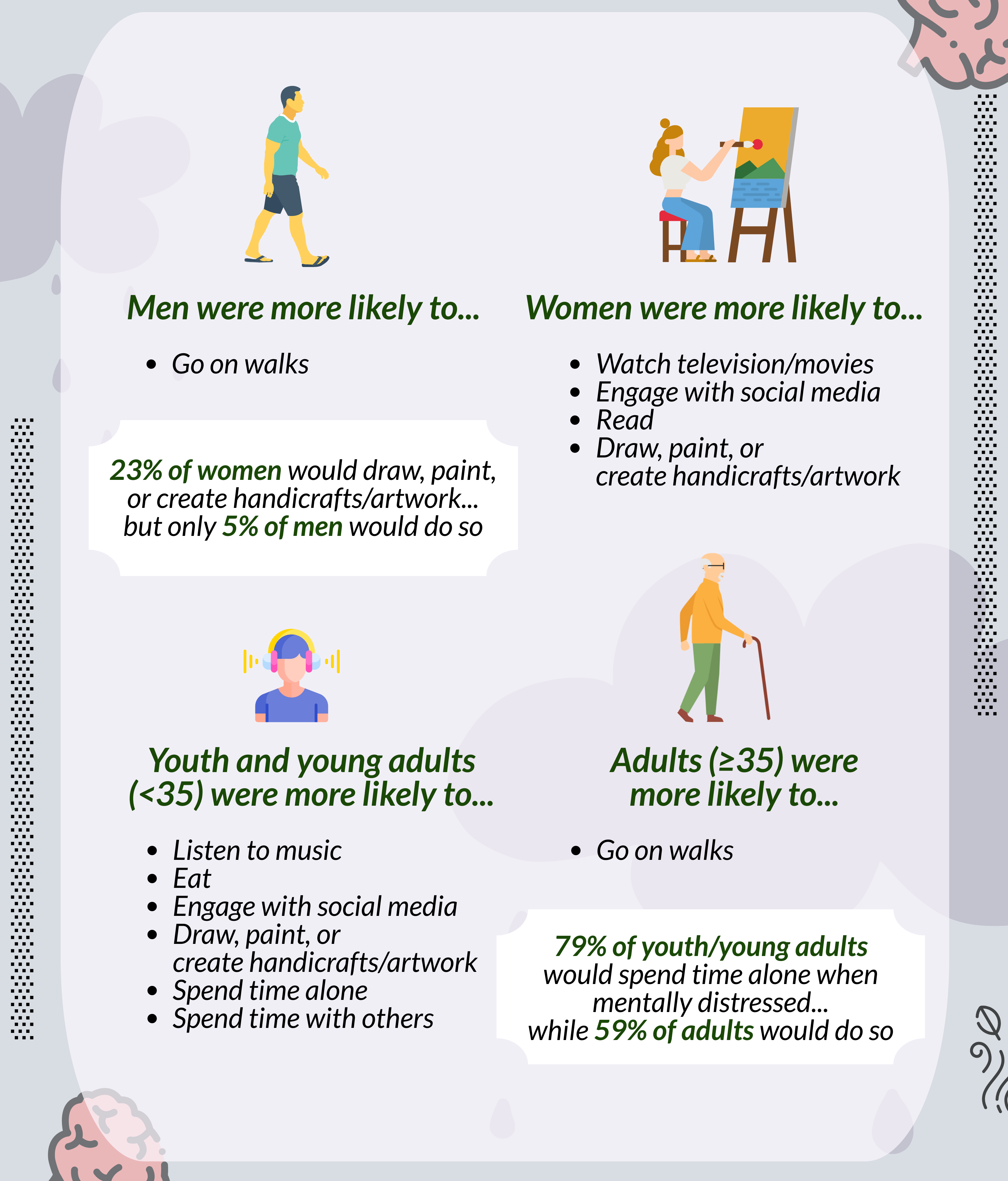

There were notable differences between demographic groups in the activities used when facing poor mental health. Notably, women and youth were significantly more likely to report using media and participating in creative endeavours, and youth were also more likely to vary their social behaviour.

On the contrary, men and adults aged 35 and above were more likely to report simply going on walks when facing poor mental health. 65% of men, for instance, reported going on walks while only 44% of women would do the same,

While the survey design imposes limitations on the findings of mental wellness habits, these trends point to women and youth generally having more varied practices for managing their mental health. However, reticence by groups of individuals in revealing their mental wellness habits may also influence the findings for this question.